Hepatitis B

| Hepatitis B | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

Electron micrograph of Hepatitis B virus |

|

| ICD-10 | B16., B18.0-B18.1 |

| ICD-9 | 070.2-070.3 |

| OMIM | 610424 |

| DiseasesDB | 5765 |

| MedlinePlus | 000279 |

| eMedicine | med/992 ped/978 |

| MeSH | D006509 |

Hepatitis B is an infectious illness caused by hepatitis B virus (HBV) which infects the liver of hominoidae, including humans, and causes an inflammation called hepatitis. Originally known as "serum hepatitis",[1] the disease has caused epidemics in parts of Asia and Africa, and it is endemic in China.[2] About a third of the world's population, more than 2 billion people, have been infected with the hepatitis B virus.[3] This includes 350 million chronic carriers of the virus.[4] Transmission of hepatitis B virus results from exposure to infectious blood or body fluids[3].

The acute illness causes liver inflammation, vomiting, jaundice and—rarely—death. Chronic hepatitis B may eventually cause liver cirrhosis and liver cancer—a fatal disease with very poor response to current chemotherapy.[5] The infection is preventable by vaccination.[6]

Hepatitis B virus is an hepadnavirus—hepa from hepatotrophic and dna because it is a DNA virus[7]—and it has a circular genome composed of partially double-stranded DNA. The viruses replicate through an RNA intermediate form by reverse transcription, and in this respect they are similar to retroviruses.[8] Although replication takes place in the liver, the virus spreads to the blood where virus-specific proteins and their corresponding antibodies are found in infected people. Blood tests for these proteins and antibodies are used to diagnose the infection.[9]

Contents |

Signs and symptoms

Acute infection with hepatitis B virus is associated with acute viral hepatitis – an illness that begins with general ill-health, loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, body aches, mild fever, dark urine, and then progresses to development of jaundice. It has been noted that itchy skin has been an indication as a possible symptom of all hepatitis virus types. The illness lasts for a few weeks and then gradually improves in most affected people. A few patients may have more severe liver disease (fulminant hepatic failure), and may die as a result of it. The infection may be entirely asymptomatic and may go unrecognized.

Chronic infection with hepatitis B virus may be either asymptomatic or may be associated with a chronic inflammation of the liver (chronic hepatitis), leading to cirrhosis over a period of several years. This type of infection dramatically increases the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma (liver cancer). Chronic carriers are encouraged to avoid consuming alcohol as it increases their risk for cirrhosis and liver cancer. Hepatitis B virus has been linked to the development of Membranous glomerulonephritis (MGN).[10]

Mechanisms

Pathogenesis

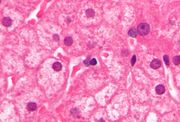

The hepatitis B virus primarily interferes with the functions of the liver by replicating in liver cells, known as hepatocytes.

The receptor is not yet known, though there is evidence that the receptor in the closely related duck hepatitis B virus is carboxypeptidase D.[11][12] HBV virions (DANE particle) bind to the host cell via the preS domain of the viral surface antigen and are subsequently internalized by endocytosis. PreS and IgA receptors are accused of this interaction. HBV-preS specific receptors are primarily expressed on hepatocytes; however, viral DNA and proteins have also been detected in extrahepatic sites, suggesting that cellular receptors for HBV may also exist on extrahepatic cells.

During HBV infection, the host immune response causes both hepatocellular damage and viral clearance. Although the innate immune response does not play a significant role in these processes, the adaptive immune response, particularly virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs), contributes to most of the liver injury associated with HBV infection. By killing infected cells and by producing antiviral cytokines capable of purging HBV from viable hepatocytes, CTLs eliminate the virus.[13] Although liver damage is initiated and mediated by the CTLs, antigen-nonspecific inflammatory cells can worsen CTL-induced immunopathology, and platelets activated at the site of infection may facilitate the accumulation of CTLs in the liver.[14]

Transmission

Transmission of hepatitis B virus results from exposure to infectious blood or body fluids containing blood. Possible forms of transmission include unprotected sexual contact, blood transfusions, re-use of contaminated needles & syringes, and vertical transmission from mother to child during childbirth. Without intervention, a mother who is positive for HBsAg confers a 20% risk of passing the infection to her offspring at the time of birth. This risk is as high as 90% if the mother is also positive for HBeAg. HBV can be transmitted between family members within households, possibly by contact of nonintact skin or mucous membrane with secretions or saliva containing HBV.[15][16] However, at least 30% of reported hepatitis B among adults cannot be associated with an identifiable risk factor.[17]

Virology

Structure

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a member of the Hepadnavirus family.[7] The virus particle, (virion) consists of an outer lipid envelope and an icosahedral nucleocapsid core composed of protein. The nucleocapsid encloses the viral DNA and a DNA polymerase that has reverse transcriptase activity.[8] The outer envelope contains embedded proteins which are involved in viral binding of, and entry into, susceptible cells. The virus is one of the smallest enveloped animal viruses, with a virion diameter of 42 nm, but pleomorphic forms exist, including filamentous and spherical bodies lacking a core. These particles are not infectious and are composed of the lipid and protein that forms part of the surface of the virion, which is called the surface antigen (HBsAg), and is produced in excess during the life cycle of the virus.[18]

Genome

The genome of HBV is made of circular DNA, but it is unusual because the DNA is not fully double-stranded. One end of the full length strand is linked to the viral DNA polymerase. The genome is 3020–3320 nucleotides long (for the full-length strand) and 1700–2800 nucleotides long (for the short length-strand).[19] The negative-sense, (non-coding), is complementary to the viral mRNA. The viral DNA is found in the nucleus soon after infection of the cell. The partially double-stranded DNA is rendered fully double-stranded by completion of the (+) sense strand and removal of a protein molecule from the (-) sense strand and a short sequence of RNA from the (+) sense strand. Non-coding bases are removed from the ends of the (-) sense strand and the ends are rejoined. There are four known genes encoded by the genome, called C, X, P, and S. The core protein is coded for by gene C (HBcAg), and its start codon is preceded by an upstream in-frame AUG start codon from which the pre-core protein is produced. HBeAg is produced by proteolytic processing of the pre-core protein. The DNA polymerase is encoded by gene P. Gene S is the gene that codes for the surface antigen (HBsAg). The HBsAg gene is one long open reading frame but contains three in frame "start" (ATG) codons that divide the gene into three sections, pre-S1, pre-S2, and S. Because of the multiple start codons, polypeptides of three different sizes called large, middle, and small (pre-S1 + pre-S2 + S, pre-S2 + S, or S) are produced.[20] The function of the protein coded for by gene X is not fully understood but it is associated with the development of liver cancer. It stimulates genes that promote cell growth and inactivates growth regulating molecules.[21]

Replication

The life cycle of hepatitis B virus is complex. Hepatitis B is one of a few known non-retroviral viruses which use reverse transcription as a part of its replication process. The virus gains entry into the cell by binding to an unknown receptor on the surface of the cell and enters it by endocytosis. Because the virus multiplies via RNA made by a host enzyme, the viral genomic DNA has to be transferred to the cell nucleus by host proteins called chaperones. The partially double stranded viral DNA is then made fully double stranded and transformed into covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA) that serves as a template for transcription of four viral mRNAs. The largest mRNA, (which is longer than the viral genome), is used to make the new copies of the genome and to make the capsid core protein and the viral DNA polymerase. These four viral transcripts undergo additional processing and go on to form progeny virions which are released from the cell or returned to the nucleus and re-cycled to produce even more copies.[20][22] The long mRNA is then transported back to the cytoplasm where the virion P protein synthesizes DNA via its reverse transcriptase activity.

Serotypes and genotypes

The virus is divided into four major serotypes (adr, adw, ayr, ayw) based on antigenic epitopes presented on its envelope proteins, and into eight genotypes (A-H) according to overall nucleotide sequence variation of the genome. The genotypes have a distinct geographical distribution and are used in tracing the evolution and transmission of the virus. Differences between genotypes affect the disease severity, course and likelihood of complications, and response to treatment and possibly vaccination.[23][24]

Genotypes differ by at least 8% of their sequence and were first reported in 1988 when six were initially described (A-F).[25] Two further types have since been described (G and H).[26] Most genotypes are now divided into subgenotypes with distinct properties.[27]

Genotype A is most commonly found in the Americas, Africa, India and Western Europe. Genotype B is most commonly found in Asia and the United States. Genotype B1 dominates in Japan, B2 in China and Vietnam while B3 confined to Indonesia. B4 is confined to Vietnam. All these strains specify the serotype ayw1. B5 is most common in the Philippines. Genotype C is most common in Asia and the United States. Subgenotype C1 is common in Japan, Korea and China. C2 is common in China, South-East Asia and Bangladesh and C3 in Oceania. All these strains specify the serotype adrq. C4 specifying ayw3 is found in Aborigines from Australia.[28] Genotype D is most commonly found in Southern Europe, India and the United States and has been divided into 8 subtypes (D1-D8). In Turkey genotype D is also the most common type. A pattern of defined geographical distribution is less evident with D1-D4 where these subgenotypes are widely spread within Europe, Africa and Asia. This may be due to their divergence having occurred before than of genotypes B and C. D4 appears to be the oldest split and is still the dominating subgenotype of D in Oceania. Type E is most commonly found in West and Southern Africa. Type F is most commonly found in Central and South America and has been divided into two subgroups (F1 and F2). Genotype G has an insertion of 36 nucleotides in the core gene and is found in France and the United States.[29]Type H is most commonly found in Central and South America and California in United States. Africa has five genotypes (A-E). Of these the predominant genotypes are A in Kenya, B and D in Egypt, D in Tunisia, A-D in South Africa and E in Nigeria.[28] Genotype H is probably split off from genotype F within the New World.[30]

Diagnosis

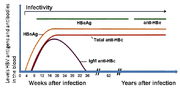

The tests, called assays, for detection of hepatitis B virus infection involve serum or blood tests that detect either viral antigens (proteins produced by the virus) or antibodies produced by the host. Interpretation of these assays is complex.[9]

The hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) is most frequently used to screen for the presence of this infection. It is the first detectable viral antigen to appear during infection. However, early in an infection, this antigen may not be present and it may be undetectable later in the infection as it is being cleared by the host. The infectious virion contains an inner "core particle" enclosing viral genome. The icosahedral core particle is made of 180 or 240 copies of core protein, alternatively known as hepatitis B core antigen, or HBcAg. During this 'window' in which the host remains infected but is successfully clearing the virus, IgM antibodies to the hepatitis B core antigen (anti-HBc IgM) may be the only serological evidence of disease.

Shortly after the appearance of the HBsAg, another antigen named as the hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) will appear. Traditionally, the presence of HBeAg in a host's serum is associated with much higher rates of viral replication and enhanced infectivity; however, variants of the hepatitis B virus do not produce the 'e' antigen, so this rule does not always hold true. During the natural course of an infection, the HBeAg may be cleared, and antibodies to the 'e' antigen (anti-HBe) will arise immediately afterwards. This conversion is usually associated with a dramatic decline in viral replication.

If the host is able to clear the infection, eventually the HBsAg will become undetectable and will be followed by IgG antibodies to the hepatitis B surface antigen and core antigen, (anti-HBs and anti HBc IgG).[7] The time between the removal of the HBsAg and the appearance of anti-HBs is called the window period. A person negative for HBsAg but positive for anti-HBs has either cleared an infection or has been vaccinated previously.

Individuals who remain HBsAg positive for at least six months are considered to be hepatitis B carriers.[31] Carriers of the virus may have chronic hepatitis B, which would be reflected by elevated serum alanine aminotransferase levels and inflammation of the liver, as revealed by biopsy. Carriers who have seroconverted to HBeAg negative status, particularly those who acquired the infection as adults, have very little viral multiplication and hence may be at little risk of long-term complications or of transmitting infection to others.[32]

PCR tests have been developed to detect and measure the amount of HBV DNA, called the viral load, in clinical specimens. These tests are used to assess a person's infection status and to monitor treatment.[33] Individuals with high viral loads, characteristically have ground glass hepatocytes on biopsy.

Prevention

Several vaccines have been developed by Maurice Hilleman for the prevention of hepatitis B virus infection. These rely on the use of one of the viral envelope proteins (hepatitis B surface antigen or HBsAg). The vaccine was originally prepared from plasma obtained from patients who had long-standing hepatitis B virus infection. However, currently, it is made using a synthetic recombinant DNA technology that does not contain blood products. You cannot catch hepatitis B from this vaccine.[34]

Following vaccination, hepatitis B surface antigen may be detected in serum for several days; this is known as vaccine antigenaemia.[35] The vaccine is administered in either two-, three-, or four-dose schedules into infants and adults, which provides protection for 85–90% of individuals.[36] Protection has been observed to last 12 years in individuals who show adequate initial response to the primary course of vaccinations, and that immunity is predicted to last at least 25 years.[37]

Unlike hepatitis A, hepatitis B does not generally spread through water and food. Instead, it is transmitted through body fluids; prevention is thus the avoidance of such transmission: unprotected sexual contact, blood transfusions, re-use of contaminated needles and syringes, and vertical transmission during child birth. Infants may be vaccinated at birth.[38]

Shi, et al showed that besides the WHO recommended joint immunoprophylaxis starting from the newborn, multiple injections of small doses of hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIg, 200–400 IU per month)[39][40], or oral lamivudine (100 mg per day) in HBV carrier mothers with a high degree of infectiousness (>106 copies/ml) in late pregnancy (the last three months of pregnancy)[41][42], effectively and safely prevent HBV intrauterine transmission, which provide new insight into prevention of HBV at the earliest stage.

Treatment

Acute hepatitis B infection does not usually require treatment because most adults clear the infection spontaneously.[43] Early antiviral treatment may only be required in fewer than 1% of patients, whose infection takes a very aggressive course (fulminant hepatitis) or who are immunocompromised. On the other hand, treatment of chronic infection may be necessary to reduce the risk of cirrhosis and liver cancer. Chronically infected individuals with persistently elevated serum alanine aminotransferase, a marker of liver damage, and HBV DNA levels are candidates for therapy.[44]

Although none of the available drugs can clear the infection, they can stop the virus from replicating, thus minimizing liver damage. Currently, there are seven medications licensed for treatment of hepatitis B infection in the United States. These include antiviral drugs lamivudine (Epivir), adefovir (Hepsera), tenofovir (Viread), telbivudine (Tyzeka) and entecavir (Baraclude) and the two immune system modulators interferon alpha-2a and PEGylated interferon alpha-2a (Pegasys). The use of interferon, which requires injections daily or thrice weekly, has been supplanted by long-acting PEGylated interferon, which is injected only once weekly.[45] However, some individuals are much more likely to respond than others and this might be because of the genotype of the infecting virus or the patient's heredity. The treatment reduces viral replication in the liver, thereby reducing the viral load (the amount of virus particles as measured in the blood).[46]

Infants born to mothers known to carry hepatitis B can be treated with antibodies to the hepatitis B virus (HBIg). When given with the vaccine within twelve hours of birth, the risk of acquiring hepatitis B is reduced 90%.[47] This treatment allows a mother to safely breastfeed her child.

Response to treatment differs between the genotypes. Interferon treatment may produce an e antigen seroconversion rate of 37% in genotype A but only a 6% seroconversion in type D. Genotype B has similar seroconversion rates to type A while type C seroconverts only in 15% of cases. Sustained e antigen loss after treatment is ~45% in types A and B but only 25–30% in types C and D.[48]

In July 2005, researchers identified an association between a host-derived DNA-binding protein and the amount of HBV replication in the liver. Controlling the level of production of this protein could be used to treat hepatitis B.[49]

Prognosis

Hepatitis B virus infection may either be acute (self-limiting) or chronic (long-standing). Persons with self-limiting infection clear the infection spontaneously within weeks to months.

Children are less likely than adults to clear the infection. More than 95% of people who become infected as adults or older children will stage a full recovery and develop protective immunity to the virus. However, this drops to 30% for younger children, and only 5% of newborns that acquire the infection from their mother at birth will clear the infection[50]. This population has a 40% lifetime risk of death from cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma.[45] Of those infected between the age of one to six, 70% will clear the infection.[51]

Hepatitis D (HDV) can only occur with a concomitant hepatitis B infection, because HDV uses the HBV surface antigen to form a capsid.[52] Co-infection with hepatitis D increases the risk of liver cirrhosis and liver cancer.[53] Polyarteritis nodosa is more common in people with hepatitis B infection.

Reactivation

Hepatitis B virus DNA persists in the body after infection and in some people the disease recurs.[54] Although rare, reactivation is seen most often in people with impaired immunity.[55] HBV goes through cycles of replication and non-replication. Approximately 50% of patients experience acute reactivation. Male patients with baseline ALT of 200 UL/L are three times more likely to develop a reactivation than patients with lower levels. Patients who undergo chemotherapy are at risk for HBV reactivation. The current view is that immunosuppressive drugs favor increased HBV replication while inhibiting cytotoxic T cell function in the liver.[56]

Epidemiology

|

no data ≤ 10 10–20 20–30 30–40 40–50 50–80

|

80–100 100–120 120–150 150–200 200–500 ≥ 500

|

As of 2004, there are an estimated 350 million HBV infected individuals worldwide. National and regional prevalence ranges from over 10% in Asia to under 0.5% in the United States and northern Europe. Routes of infection include vertical transmission (such as through childbirth), early life horizontal transmission (bites, lesions, and sanitary habits), and adult horizontal transmission (sexual contact, intravenous drug use).[58] The primary method of transmission reflects the prevalence of chronic HBV infection in a given area. In low prevalence areas such as the continental United States and Western Europe, injection drug abuse and unprotected sex are the primary methods, although other factors may also be important.[59] In moderate prevalence areas, which include Eastern Europe, Russia, and Japan, where 2–7% of the population is chronically infected, the disease is predominantly spread among children. In high prevalence areas such as China and South East Asia, transmission during childbirth is most common, although in other areas of high endemicity such as Africa, transmission during childhood is a significant factor.[60] The prevalence of chronic HBV infection in areas of high endemicity is at least 8%.

History

The earliest record of an epidemic caused by hepatitis B virus was made by Lurman in 1885.[61] An outbreak of smallpox occurred in Bremen in 1883 and 1,289 shipyard employees were vaccinated with lymph from other people. After several weeks, and up to eight months later, 191 of the vaccinated workers became ill with jaundice and were diagnosed as suffering from serum hepatitis. Other employees who had been inoculated with different batches of lymph remained healthy. Lurman's paper, now regarded as a classical example of an epidemiological study, proved that contaminated lymph was the source of the outbreak. Later, numerous similar outbreaks were reported following the introduction, in 1909, of hypodermic needles that were used, and more importantly reused, for administering Salvarsan for the treatment of syphilis. The virus was not discovered until 1965 when Baruch Blumberg, then working at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), discovered the Australia antigen (later known to be hepatitis B surface antigen, or HBsAg) in the blood of Australian aboriginal people.[62] Although a virus had been suspected since the research published by MacCallum in 1947[63], D.S. Dane and others discovered the virus particle in 1970 by electron microscopy.[64] By the early 1980s the genome of the virus had been sequenced,[65] and the first vaccines were being tested.[66]

See also

- Hepatitis A

- Hepatitis B in China

- Hepatitis C

- Hepatitis D

- Hepatitis E

- Hepatitis F

- Hepatitis G

- Jade Ribbon Campaign

- Maurice Hilleman

- Baruch S. Blumberg

- World Hepatitis Day

References

- ↑ doi:10.1001/jama.276.10.841

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ doi:10.1002/hep.21347

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Hepatitis B". World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs204/en/index.html. Retrieved 2009-09-19.

- ↑ "FAQ about Hepatitis B". Stanford School of Medicine. 2008-07-10. http://liver.stanford.edu/Education/faq.html. Retrieved 2009-09-19.

- ↑ doi:10.1016/j.siny.2007.01.013

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ doi:10.4065/82.8.967

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Zuckerman AJ (1996). Hepatitis Viruses. In: Baron's Medical Microbiology (Baron S et al, eds.) (4th ed.). Univ of Texas Medical Branch. ISBN 0-9631172-1-1. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/bv.fcgi?rid=mmed.section.3738.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 doi:10.1055/s-2004-828672

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ 9.0 9.1 PMID 3331068 (PubMed)

Citation will be completed automatically in a few minutes. Jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ PMID 2023605 (PubMed)

Citation will be completed automatically in a few minutes. Jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ Full text at PMC: 112890

Citation will be completed automatically in a few minutes.Jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ PMID 17206752 (PubMed)

Citation will be completed automatically in a few minutes. Jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2007.01.007

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ doi:10.1038/nm1317

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ PMID 791124 (PubMed)

Citation will be completed automatically in a few minutes. Jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ "Hepatitis B – the facts: IDEAS – Victorian Government Health Information, Australia". State of Victoria. 2009-07-28. http://www.health.vic.gov.au/ideas/diseases/hepb. Retrieved 2009-09-19.

- ↑ PMID 8392167 (PubMed)

Citation will be completed automatically in a few minutes. Jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ doi:10.1099/0022-1317-67-7-1215

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2007.02.021

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ 20.0 20.1 PMID 17206754 (PubMed)

Citation will be completed automatically in a few minutes. Jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ [1] Hepatitis B virus X protein upregulates HSP90alpha expression via activation of c-Myc in human hepatocarcinoma cell line, HepG2

- ↑ PMID 17206755 (PubMed)

Citation will be completed automatically in a few minutes. Jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.10.045

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ PMID 8666521 (PubMed)

Citation will be completed automatically in a few minutes. Jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ Norder H, Courouce AM, Magnius LO (1994) Complete genomes, phylogenic relatedness and structural proteins of six strains of the hepatitis B virus, four of which represent two new genotypes. Virology 198:489–503

- ↑ Shibayama T, Masuda G, Ajisawa A, Hiruma K, Tsuda F, Nishizawa T, Takahashi M, Okamoto H (May 2005). "Characterization of seven genotypes (A to E, G and H) of hepatitis B virus recovered from Japanese patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1". Journal of Medical Virology 76 (1): 24–32. doi:10.1002/jmv.20319. PMID 15779062.

- ↑ Schaefer S (January 2007). "Hepatitis B virus taxonomy and hepatitis B virus genotypes". World Journal of Gastroenterology : WJG 13 (1): 14–21. PMID 17206751. http://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/13/14.asp.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Kurbanov F, Tanaka Y, Mizokami M (January 2010). "Geographical and genetic diversity of the human hepatitis B virus". Hepatology Research : the Official Journal of the Japan Society of Hepatology 40 (1): 14–30. doi:10.1111/j.1872-034X.2009.00601.x. PMID 20156297.

- ↑ Stuyver L, De Gendt S, Van Geyt C, Zoulim F, Fried M, Schinazi RF, Rossau R (2000) A new genotype of hepatitis B virus: complete genome and phylogenetic relatedness. J Gen Virol 81:67–74

- ↑ Arauz-Ruiz, Norder PH, Robertson BH, Magnius LO (2002) Genotype H: A new Amerindian genotype of hepatitis B virus revealed in Central America. J Gen Virol 2002, 83:2059–2073

- ↑ doi:10.1002/hep.21513

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.039

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ doi:10.1055/s-2006-951602

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ "Hepatitis B Vaccine". Doylestown, Pennsylvania: Hepatitis B Foundation. 2009-01-31. http://www.hepb.org/professionals/hepatitis_b_vaccine.htm. Retrieved 2010-03-13.

- ↑ doi:10.1086/502449

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (2006). "Chapter 18 Hepatitis B" (PDF). Immunisation Against Infectious Disease 2006 ("The Green Book") (3rd edition (Chapter 18 revised 10 October 2007) ed.). Edinburgh: Stationery Office. pp. 468. ISBN 0113225288. http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publichealth/Healthprotection/Immunisation/Greenbook/DH_4097254?IdcService=GET_FILE&dID=152019&Rendition=Web.

- ↑ doi:10.1016/j.tmaid.2006.04.004

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ O'Connor, John (2008-10-03). "Hepatitis B Prevention – The Body". Body Health Resources Corporation. http://www.thebody.com/content/art17089.html. Retrieved 2009-01-30.

- ↑ Shi Z, Li X, Ma L, Yang Y (July 2010). "Hepatitis B immunoglobulin injection in pregnancy to interrupt hepatitis B virus mother-to-child transmission-a meta-analysis". International Journal of Infectious Diseases : IJID : Official Publication of the International Society for Infectious Diseases 14 (7): e622–34. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2009.09.008. PMID 20106694.

- ↑ Li XM, Shi MF, Yang YB, Shi ZJ, Hou HY, Shen HM, Teng BQ (November 2004). "Effect of hepatitis B immunoglobulin on interruption of HBV intrauterine infection". World J Gastroenterol 10 (21): 3215–7. PMID 15457579.

- ↑ Li XM, Yang YB, Hou HY, Shi ZJ, Shen HM, Teng BQ, Li AM, Shi MF, Zou L (July 2003). "Interruption of HBV intrauterine transmission: a clinical study". World J Gastroenterol 9 (7): 1501–3. PMID 12854150.

- ↑ Shi Z, Yang Y, Ma L, Li X, Schreiber A (July 2010). "Lamivudine in late pregnancy to interrupt in utero transmission of hepatitis B virus: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Obstet Gynecol 116 (1): 147–59. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181e45951. PMID 20567182.

- ↑ Hollinger FB, Lau DT. Hepatitis B: the pathway to recovery through treatment. Gastroenterology Clinics of North America. 2006;35(4):895–931. doi:10.1016/j.gtc.2006.10.002. PMID 17129820.

- ↑ Lai CL, Yuen MF. The natural history and treatment of chronic hepatitis B: a critical evaluation of standard treatment criteria and end points. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2007;147(1):58–61. PMID 17606962.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 doi:10.1056/NEJMra0801644

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ Pramoolsinsup C. Management of viral hepatitis B. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2002;17 Suppl:S125–45. PMID 12000599.

- ↑ Libbus MK, Phillips LM. Public health management of perinatal hepatitis B virus. Public Health Nursing (Boston, Mass.). 2009;26(4):353–61. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1446.2009.00790.x. PMID 19573214.

- ↑ Cao GW. Clinical relevance and public health significance of hepatitis B virus genomic variations. World Journal of Gastroenterology : WJG. 2009;15(46):5761–9. PMID 19998495. PMC 2791267.

- ↑ doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0020163

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ Bell, S J; Nguyen, T (2009). "The management of hepatitis B" (Free full text). Aust Prescr 23 (4): 99–104. http://www.australianprescriber.com/magazine/32/4/99/104/.

- ↑ doi:10.1111/j.1399-3046.2005.00393.x

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ doi:10.1016/j.virol.2005.09.033

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ PMID 1661197 (PubMed)

Citation will be completed automatically in a few minutes. Jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ doi:10.1016/j.cld.2007.08.001

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ doi:10.1111/j.1365-2893.2007.00902.x

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ Bonacini, Maurizio, MD. "Hepatitis B Reactivation". University of Southern California Department of Surgery. http://www.surgery.usc.edu/divisions/hep/livernewsletter-reactivationofhepatitisb.html. Retrieved 2009-01-24.

- ↑ "Mortality and Burden of Disease Estimates for WHO Member States in 2002" (xls). World Health Organization. 2004-12. http://www.who.int/entity/healthinfo/statistics/bodgbddeathdalyestimates.xls.

- ↑ PMID 15602165 (PubMed)

Citation will be completed automatically in a few minutes. Jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ doi:10.1086/513435

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ doi:10.1055/s-2003-37583

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ Lurman A. (1885) Eine icterus epidemic. (In German). Berl Klin Woschenschr 22:20–3.

- ↑ PMID 5930797 (PubMed)

Citation will be completed automatically in a few minutes. Jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ MacCallum, F.O., Homologous serum hepatitis. Lancet 2, 691, (1947)

- ↑ doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(70)90926-8

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ doi:10.1038/281646a0

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ PMID 6108398 (PubMed)

Citation will be completed automatically in a few minutes. Jump the queue or expand by hand

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||